Back to Toyota

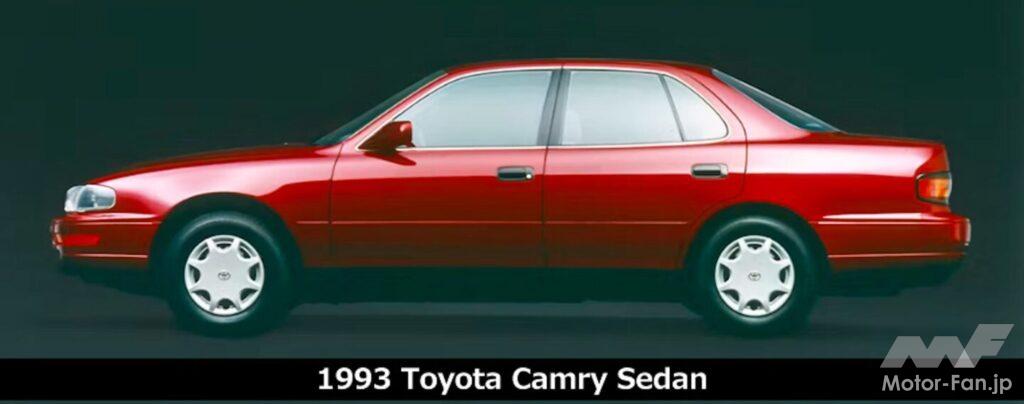

In the fall of 1986, after returning from my studies at ACCD, I rejoined the exterior design department for the first time in a while and was assigned to work on the fourth-generation Camry/Vista.

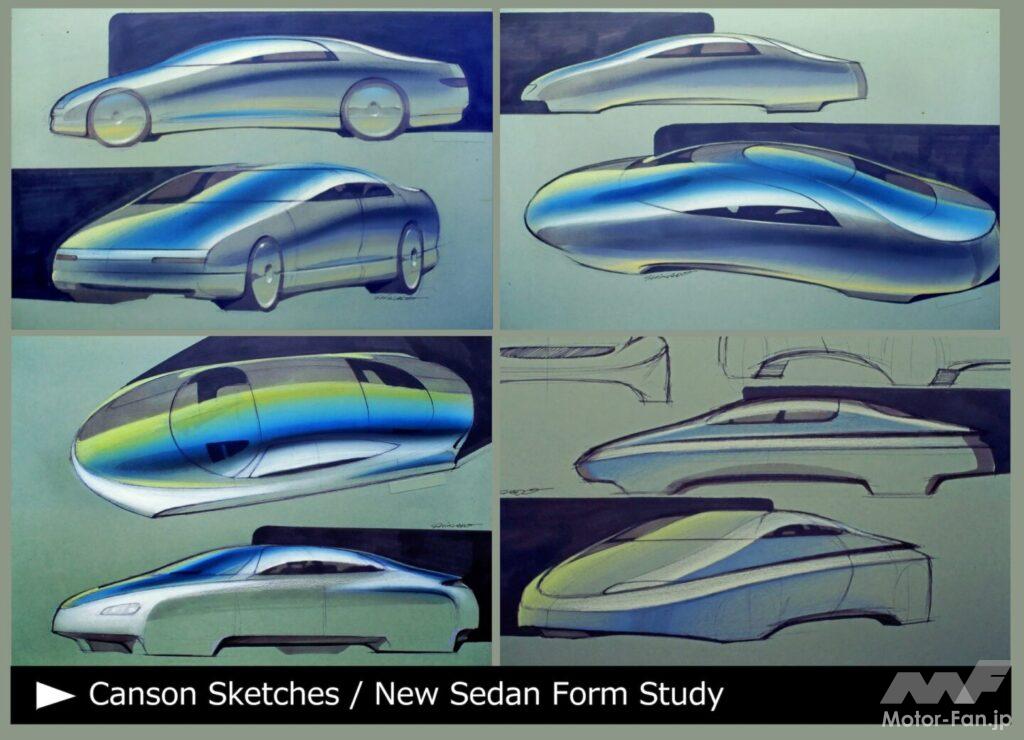

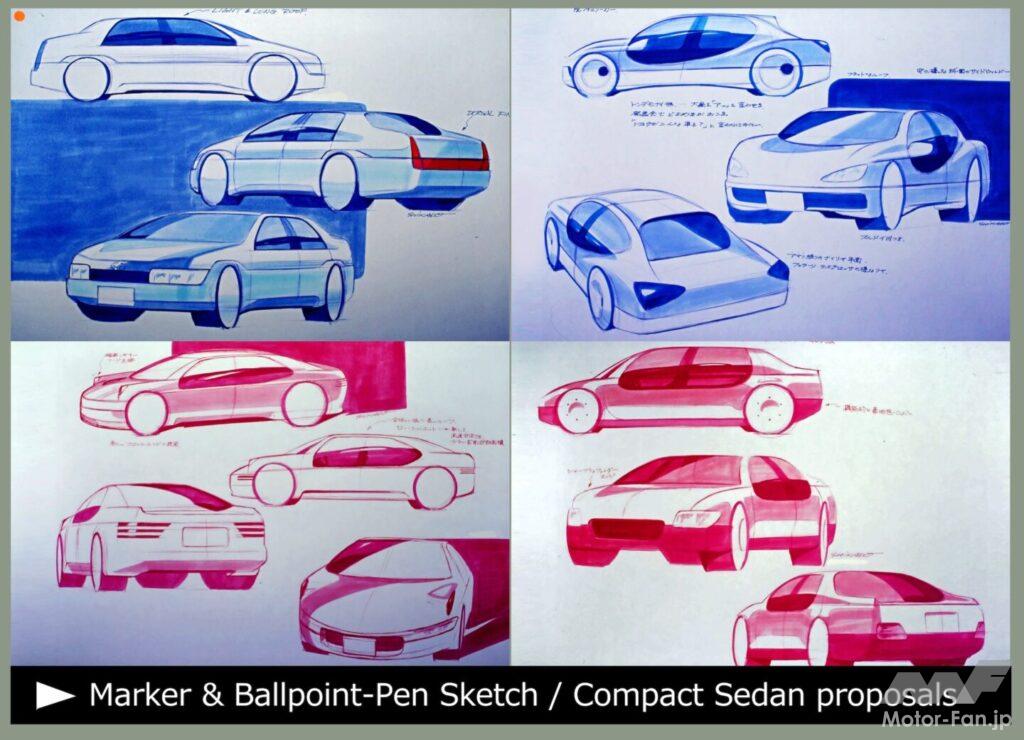

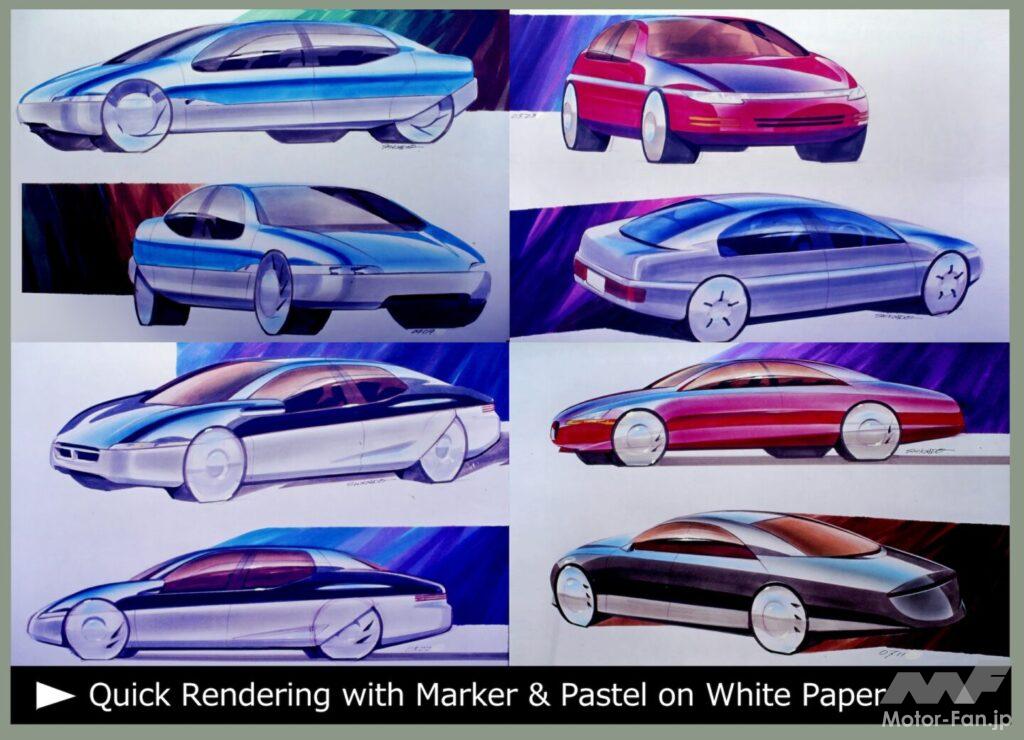

It was a fulfilling period for me — I had become accustomed to the workflow and was finally able to present my own design proposals through various methods.

At the same time, however, I began to recognize the many challenges that came with the company’s conservative policies and the realities of mass production.

Over the next eight years, I was fortunate to have opportunities to work on exterior design proposals for a variety of models, including a three-year assignment at the Toyota Tokyo Design Center, which had been established in 1990.

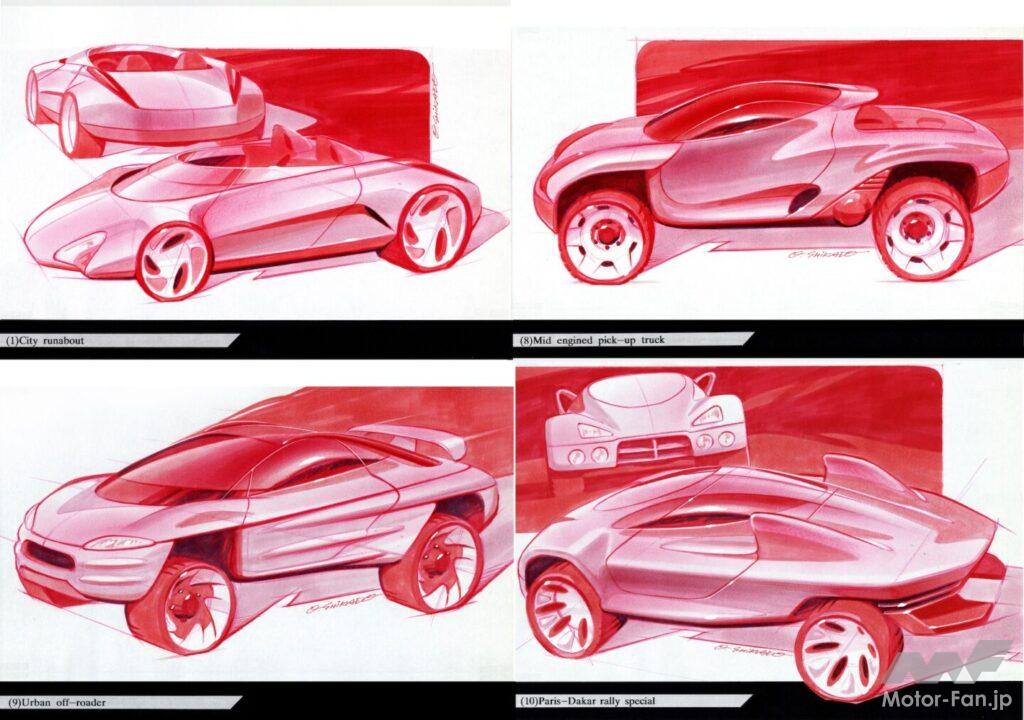

Drawing on the sketching techniques I had learned at ACCD, I devoted myself to developing new design concepts and exploring fresh creative approaches.

At that time, SUVs and minivans had not yet entered the market, so during those eight years, all the projects I worked on at Toyota were four-door sedans.

The first-generation RAV4, which I worked on during my time in Tokyo, was the only two-door vehicle, making it a particularly refreshing and enjoyable project for me.

Our Tokyo team presented two full-scale models, but in the end, the proposal selected for production came from another team within the Toyota group.

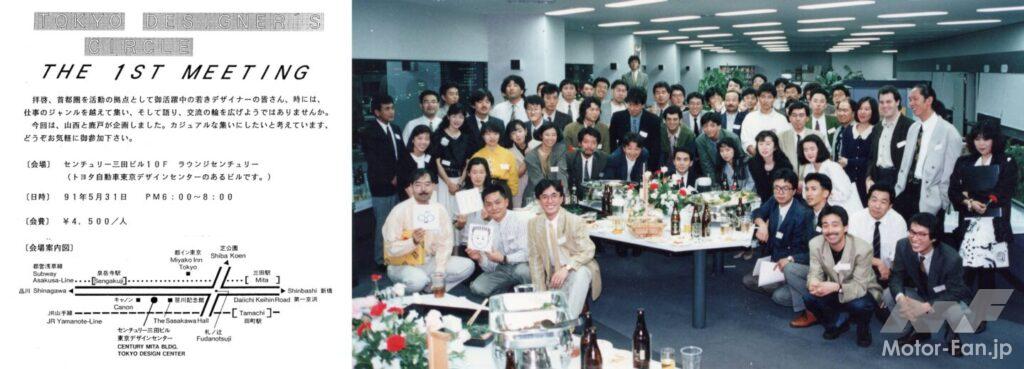

Tokyo Designers Night

In the early 1990s, many automobile manufacturers were competing to establish design studios in Tokyo.

One reason was the advantage of being in Japan’s capital — easy access to the latest lifestyle trends and cutting-edge design information.

Another major reason was recruitment. Since most car companies were based in regional cities (in other words, the countryside), having a studio in Tokyo allowed them to promote themselves to new graduates by saying, “Join our company, and you can work in Tokyo.”

Until then, designers at various automakers had almost no opportunity to interact with one another after joining their respective companies.

However, in Tokyo, nearly all major automakers had design teams located within the city. I realized that if we simply created a venue, designers from different companies could meet and exchange ideas beyond corporate boundaries.

That idea led me to establish an inter-company gathering called “Tokyo Designers Night.”

The event was held about once a year, and many of the designers I met there have remained friends to this day.

In addition, during spring break, seasonal design workshops were held at the Tokyo studio for students from design departments.

On those occasions, I sometimes gave rendering demonstrations, and one of my sketches — a 2-door sport coupé — was enlarged to full scale and exhibited in the Tokyo studio lobby alongside the scale model.

Also, being based in Tokyo provided opportunities to meet automotive magazine journalists, and I stayed in touch with several of them even after I later moved to work in the United States.

Heading Overseas at Last

In 1993, after returning from Tokyo to Toyota’s headquarters in Toyota City, I happened to have the opportunity to visit several Italian carrozzeria on business.

I visited Italdesign and IDEA, and was deeply impressed by how a small team of designers handled a wide range of projects with remarkable efficiency and creativity.

At that time, Toyota’s design department at headquarters had more than 300 design staff, and the work was highly subdivided. By then, I was in my mid-thirties and increasingly expected to take on a managerial role rather than being a hands-on creator.

After more than a decade in the company, I realized that I had yet to complete a project I could truly call my own original design, and that uncertainty began to trouble me.

After returning from Italy, I started to seriously consider working in Europe.

Although Toyota already had a design studio in Belgium, I wanted to stay longer than the typical three- or four-year company assignment — to live locally, integrate into the culture, and express my design vision directly within the European context.

But how could I reach out to the heads of European design studios and convey my intentions? In those days, before personal computers or the internet, the only means of communication were letters and faxes.

Toyota already had working relationships with several Italian carrozzeria, so I knew the names and addresses of their directors.

However, I was also aware that approaching a partner company while still employed at Toyota could be seen as inappropriate, so I decided to resign first before starting my job search.

To contact companies beyond the carrozzeria, I gathered information from senior colleagues, acquaintances, and friends who were familiar with the European design scene.

Since CDs and USB sticks didn’t exist yet, I prepared an A4-size portfolio folder containing my résumé and about ten hand-drawn sketches, and sent them by post to design studios across Europe.

Fortunately, several design directors — not only from the carrozzeria but also from a few European automakers — took the time to carefully review my portfolio and kindly replied.

A few companies even offered to interview me, so in the fall of 1993, I flew to Europe alone.

Starting in Italy and then moving on to Germany, I attended interviews with about six companies, but ultimately, I was unable to secure a position.

Looking back, my mistake was that I didn’t fully understand how the hiring process worked in Europe and the United States.

There, whether for new graduates or mid-career hires, it is rare to be judged solely on a résumé and portfolio.

It is common to have a trial period or internship — typically one to three months, and sometimes as long as six — during which the candidate actually works in the studio so that their abilities can be evaluated firsthand.

During my job search in Europe, two companies offered me such six-month internships.

However, since I had a family to support, I insisted on a formal, full-time position and declined those offers.

In hindsight, I realize that I should have accepted the internships — even with some risk — as they might have led to permanent employment later on.

And Then, to America

After completing my five-week job-hunting journey in Europe and returning to Japan, I visited Mr. H, a senior colleague who had given me valuable advice during my search.

Mr. H, who had also studied at ACCD and had professional experience in Europe, listened to my story and then asked, “Mr. Shikado, why don’t you try applying to American companies?”

During my time at ACCD, I had often heard from fellow students that obtaining a work visa to be legally employed in the United States was extremely difficult for foreigners.

At that point, I hadn’t seriously considered working in the U.S., so I had little understanding of how challenging that process could be.

However, there was no turning back now — and so, toward the end of 1993, my challenge to find a position at an American company began.

The story of my pursuit in the United States will continue in the next column.

![by Car Styling [カースタイリング]](https://motor-fan.jp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/carstyling-jp_logo.png)